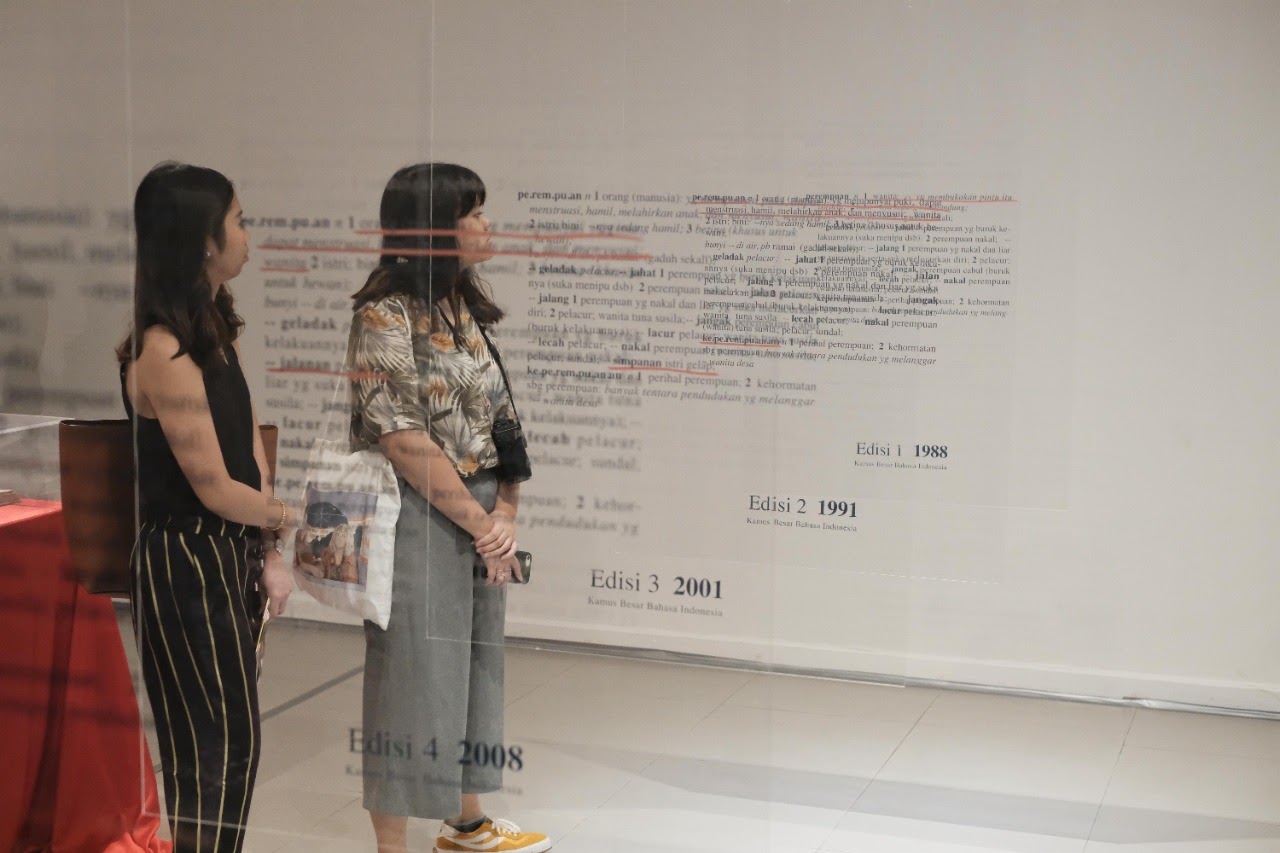

Before we talk about Ika Vantiani, let us first take a look at the image above. What do you see? See how “Perempuan” was until recently defined in the Great Dictionary of the Indonesian Language (KBBI) of the Language Center? And also notice that the definition is immediately followed by a series of composite terms containing the word Perempuan, all of them carrying negative connotations. The addition of the affixed words —Jalang, jahat, pelacur, nakal, geladak, etc”— all describe women of low virtue if not plainly eking a living from sex.

For Ika Vatiani, now an artist, this definition in a dictionary which is worshipped as “The Book” in Indonesia explains why women are often merely seen as a sexual object or reflected how the modern Indonesian society generally perceives women.

A graduate in advertising of the London School of Public Relations with 15 years of experience as a copywriter with a Creative Agency and as a freelance communication consultant, Ika has always been drawn to the topic of women, consumption, and the media. Her exposure to the topic has awakened in her, some sort of a calling, an urge to communicate to the public about women and their related issues.

Starting as a zinester in the 2000s, Ika then finally chose to voice her thoughts and ideas on this issue through collage. Collage, she believed, allowed anyone to make an art using whatever available material to illustrate their views and interpretations. She believed that people should be encouraged to voice their beliefs and opinions, including through arts, and not just be passive and accept whatever was formulated and voiced by others. Collage provided an easy way, within the reach of all, to do so.

Ika’s journey started when she took part in a networking event in Melbourne called “WANITA” back in 2015. WANITA is an Indonesian synonym for Perempuan but which, in this case, stood for Women’s Art Network Indonesia to Australia. This event’s name caught Ika’s attention and made her realize that the many Indonesian words to denote the female gender, including perempuan, wanita, cewek and betina, each carried different connotations and were linked to different experiences.

The word wanita, which is said to come from the sanskrit word vanita, or the desired one, has now taken over the respective tone that was once accorded to perempuan. It also specifically refers to adult women. Cewek, is an informal, slang version of perempuan and is in most cases used in a rather derogatory tone, expressing a low opinion or a lack of respect towards a woman. It is also exclusively used to denote younger females. Betina, except in some insulting capacities, is mostly used to denote the female gender in animals.

These differences picked Ika’s interests and prompted her to examine the development of the definition of “Perempuan”, the more classical term for women, in KBBI, from its first to fifth volumes. The KBBI is regularly revised and updated and it is currently on its fifth volume. But to her disappointment, she found out was that there have been no changes at all and the definition continued to stick and to revolve around sex and the reproductive process only.

For Ika, the word for woman, Perempuan, is one with an extraordinary etymology. The root of the word is “Empu” which means master, or someone who is a master at a particular skill. Another theory says that the root of the word was “ampu” which means support. But whether the root word was Empu or Ampu, the resulting word “Perempuan” carried a respectful undertone. Unfortunately, the word has since then experienced a degradation, losing the respectful aspect and slipping to the level as defined in the KBBI — primarily linked to sex and the reproductive process.

Ika then went on and held a workshop in Melbourne with the theme of “Kata untuk Perempuan,” to research how the public perceived the word “Perempuan.” The results of this workshop were very diverse, prompting Ika to further extend the project. In 2016, Ika decided to take the workshop to Indonesia. After two years of doing workshops, Ika then created a project, Perempuan dalam Kamus Bahasa Indonesia, as her final assignment to graduate from an art school. Recalling her findings in 2015 while working on the Kata Untuk Perempuan project, Ika came to question why the word “Perempuan” should be described in that way.

For her final assignment, Ika invited her friend Yolando Siahaya, a creative director, to work on an art installation of her first exhibition of Perempuan dalam Kamus Bahasa Indonesia at the National Gallery.

In this exhibition, Ika exhibited her findings in the form of KBBI books from the 50s to the present, showing how the definition of “Perempuan” was defined only by sex. For her, it was important to engage in artivism to promote the problem, considering that the KBBI is seen as the most complete and accurate language source ever published by the Government of the Republic of Indonesia. She also exhibited her writings on acrylic, as well as some of her collage arts.

Their artivism approach was by showcasing the definition of “Perempuan” in KBBI books from the 80s edition to the present on transparent acrylic sheets. Through this installation, both Ika and Yolando wanted people to see how shocking the definition of “Perempuan” has remained through time, even in the most complete and accurate official language reference book.

Photo 2. Perempuan dalam Kamus Bahasa Indonesia installation

Ika and Yolando’s journey did not stop here. In 2020, Ika Vantiani joined the Women’s March by wearing a protest “Ganti penjelasan kata ‘Perempuan’ dalam KBBI!” printed on a white t-shirt. Although they made the shirt solely for this one occasion, the t-shirt received positive responses, prompting them to make more and sell them. Many women bought the Tshirt and expressed their support by wearing them on social media.

One of the highlights of this movement was when Asteriska, a singer and influencer uploaded her photo wearing the t-shirt on her Instagram in early 2021. This post attracted public attention even more, including the media, Komnas Perempuan, and even government institutions. This was also believed to have been one of the reasons behind the move by the Language Agency to finally change the definition of “Perempuan”.

Photo 3. Asteriska’s post expressing her protest and tagging all relevant parties

In April 2021, the Language Agency made substantial changes to the definition. Everyone can now see the changes in KBBI online. “Perempuan” is now defined as “orang (manusia) yang mempunyai vagina, biasanya dapat menstruasi, hamil, melahirkan anak, atau menyusui; wanita; puan” (a person who possesses a vagina, and usually can experience menstruation, give birth to a child or breastfeed; wanita; puan). The addition of the words “puan” and “biasanya (usually)” gives it a more inclusive and respectful meaning.

Photo 4. The definition of “Perempuan” from KBBI Daring.

And following the updated definition, came a new set of composite words that still contained “perempuan” but that carried a more balanced and positive image of women. Instead of just containing sex-related composite words, terms disuch as “perempuan adat, perempuan besi, perempuan idaman, perempuan karier, perempuan suci dan perempuan tangguh” (Customary woman, iron woman, ideal woman, career woman, holy woman and strong woman) were included.

Although the changes were still only in the online KBBI, and could only be accessed by those who have an account with the KBBI, this was still a milestone for Ika Vantiani’s artivism. But for her, this project was not yet finished and remained ongoing. It was interesting to note that while it took her years to struggle to change the definition of “Perempuan” in the KBBI, the support of just one influencer with a lot of followers, managed to bring about a change in just a few months.

And judging from the public response, there appeared to be a growing awareness about the issue and what needed to be done to improve the definition and perception of women and attitudes towards women. The changes in the KBBI definition were also expected to boost the confidence of women at work, and encourage them to prove that yes, there were a lot of positive aspects of being a woman and that women could also become tough, career women, iron ladies.

So, what do you think? Are changes in the definition of a woman in a reference dictionary enough to shift perceptions about women and their role in society? To get to know Ika Vantiani’s journey in becoming an art practitioner and her struggle to get more positive recognition for women, watch Ika Vantiani’s video of her addressing a PechaKucha event on IGTV @Mavgram.