The marketers at Sensodyne no doubt wanted their brand campaign to go viral.

They achieved this objective but not in the way they wanted because their virality quickly turned into a vulnerability for their brand. In this incident lies a lesson for all marketing communicators that attention can be easy to get but getting the right attention is something else.

What happened?

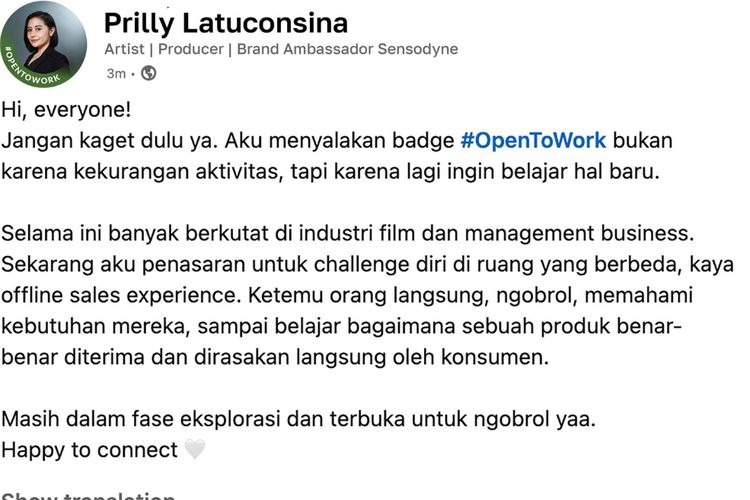

At the end of January fans and followers of actress and entrepreneur Prilly Latuconsina were surprised when she activated an #OpenToWork badge on Linkedin and announced she was exploring sales and marketing roles outside the entertainment industry. Her use of the #OpenToWork badge struck a chord with her audience, many of whom personally or had friends use that same badge in these anxious and difficult economic times. Her profile was flooded with 30,000+ connection requests and job offers.

Then, a few days later, Prilly appeared at a Sensodyne promotional event as a “sales representative” revealing that her looking for a new job had been just a marketing gimmick. Fans felt manipulated and responded with criticism. The virality of the campaign quickly turned malignant to the brand.

The question that needs to be asked here is why brands march toward folly. Sensodyne should be a brand built on understanding sensitivity, empathy toward people experiencing real vulnerability. Yet it chose a march of folly toward a quick win of virality over building trust for its brand.

In a polyperma world, character is your only anchor

The only plausible answer is that while the brand lacks a North star to guide what it should say and do, and most importantly, not do. This is something that the usual trappings of brands–brand equity, brand values and maybe even vision and mission is inadequate to do.

What is needed for the brand is to define its corporate character, a concept advanced by the prestigious Page Society, so that everyone who works in and on it - the brand directors, managers and their communication agencies all know what the brand should sound like, feel like, look like and act like. It is no different from the character of a person informing them on everything they do,say or how they go about doing so.

This is especially important because we are living in a world vulnerable to polyperma crises.

We have written before about how the old rules of crisis management no longer apply. In an age of polyperma crises, where organizations face perpetual storms fueled by social media and polarized societies, traditional playbooks centered on “controlling the narrative” have lost their power.

In this polyperma world, you can’t please everyone. The question for brands shouldn’t be: “How do we avoid all criticism”, but rather, “What do we stand for, and does this campaign align with that?”

For Sensodyne, a brand built on understanding sensitivity, the character test should have been simple: Does this demonstrate empathy toward people experiencing real vulnerability? Does it add value to the community they claim to care about?

Corporate character isn’t a PR tactic. It’s the belief system of our organization. It tells you not just what to say when things go wrong, but what you should never do in the first place. Because in a world where you can’t control the narrative, the only currency you have left is trust. Built through consistent alignment between your values and your actions.

A reminder for all of us

This isn’t about one misstep. It’s about a pattern we’ve seen or worse, even participated in: the rush to be talked about often drowns the question of who we are talking to, and what we are actually saying to them.

As PR practitioners, we shape narratives. That influence isn’t neutral. It comes with weight.

So before the next pitch deck promises “massive engagement”, maybe we pause and ask:

- Does this add something meaningful, or just more clutter?

- Are we building trust, or just manufacturing moments?

- Will they trust us more after this, or just remember us louder?

These aren’t rhetorical questions. They’re guardrails. Because our work isn’t measured by how many times something trends. It’s measured by whether people still trust us when the trending stops.

And trust, once broken, doesn’t go viral. It just goes away.